Showing posts with label marine life. Show all posts

Showing posts with label marine life. Show all posts

Wednesday 7 December 2016

Dutch-owned 'super' trawler "Geelong Star" has left Australian waters and will not be returning

Save Our Marine Life is celebrating the fact that the Dutch-owned factory trawler Geelong Star has left Australian waters and will not be returning.

The trawler has removed its Australian flag of convenience and been reflagged as Dutch – in the process its old name KW 172 Dirk Dirk has been re-instated.

ABC News reported on 24 November 2016 that:

The ship's departure came just before Labor and Greens members on a Senate committee recommended all mid-water trawlers be banned from fishing in Australian waters.

The committee had been investigating the environmental, social and economic impacts of super trawlers.

In 2012, ships known as super trawlers were prohibited from fishing in Australian waters, but the ban only applied to vessels over 130 metres, and not the Geelong Star, which is 95 metres.

Labor and Greens committee members also urged the Federal Government to appoint a National Recreational Fishing Council.

The report said public confidence in the management of Australia's fisheries needed to be enhanced, and it suggested the Australian Fisheries Management Authority publish information about fishing activity in the Small Pelagic Fishery regularly, such as bycatch quantities.

Liberal Senators Jonathon Duniam and David Bushby dissented from the recommendations, and said the Government was "committed to maintaining a balanced and science-based approach to all decisions regarding access to Commonwealth fisheries".

The Senate Standing Committees on Environment

and Communications report into the Environmental, social and economic

impacts of large-capacity fishing vessels commonly known as 'Supertrawlers'

operating in Australia's marine jurisdiction was published in November 2016.

The Committee

report stated:

1.46 The FV Geelong Star commenced

fishing in the SPF on 2 April 2015.40 The Geelong Star is

a 3181 tonne factory freezer vessel with a hold capacity of 1061 tonnes. At

95.18 metres, the Geelong Star is the longest fishing vessel

in the AFZ.41

1.47 The operation of the Geelong

Star in the SPF is a joint enterprise between Seafish Tasmania and

Dutch company Parlevliet & Van der Plas BV and its Australian subsidiary,

Seafish Tasmania Pelagic Pty Ltd.42 The fish caught by the Geelong

Star is shipped to export markets, usually in West Africa.43

1.48 AFMA was notified that Seafish

Tasmania had nominated the Geelong Star to fish its

concessions in the SPF on 12 February 2015. Following registration of the Geelong

Star as an Australian-flagged boat by the Australian Maritime Safety

Authority,44 AFMA confirmed that the vessel met its

requirements. The Geelong Star commenced fishing in the SPF on

2 April 2015. As the Geelong Star is less than 130 metres in

length, it is not affected by the ban introduced by the government in April

2015….

1.50 Since it commenced operating, AFMA

has initiated various regulatory measures in response to mortalities of

protected species caused by the operations of the Geelong Star.

Various stakeholders are also concerned about the effect of the trawler's

operations on other commercial fishing operations and recreational fishing

activities. Both the fishing activities of the Geelong Star and

the regulatory approach taken by AFMA have attracted controversy.

1.51 Environmental non-government

organisations expressed opposition to the activities of the Geelong

Star and the approach taken to managing the SPF. Environment Tasmania

and the Australian Marine Conservation Society both called on the government to

'enact a permanent ban on the operation of factory freezer trawlers in the

Small Pelagic Fishery'.45 The Conservation Council SA provided

a list of recommendations regarding potential localised depletion, adverse

environmental effects, how to minimise impacts on protected species and the

presence of AFMA observers on the vessel. The Conservation Council SA called

for vessels such as the Geelong Star to be banned from the

fishery 'until management strategies', including the recommendations outlined

in its submission, 'are in place to effectively minimise impacts on protected

species'.46

1.52 Recreational fishing interests are

another key stakeholder group. Submitters in this group expressed concern about

potential repercussions for the Australian recreational fishing sector from the

operations of the Geelong Star. The Australian Recreational Fishing

Foundation (ARFF) called for a moratorium on 'industry scale' fishing in areas

of the SPF that are of concern to the recreational fishing sector. The ARFF

argued that this moratorium should remain in place 'until a comprehensive

assessment has been conducted to determine whether industrial scale fishing of

the SPF is the highest and best use of the SPF, in our nation's interest and

whether the small pelagic fishery should be commercially fished at all'.47

1.53 Seafish Tasmania, the operator of

the Geelong Star, argued that the use of a factory freezer trawler

such as the Geelong Star is the only way that operations in

the SPF can be commercially viable. Seafish Tasmania also advised that, over 11

years, it has worked within the regulatory arrangements to assist in developing

management plans and strategies 'that support the sustainable management of the

SPF'.48 Seafish Tasmania added:

The current management regime in the

SPF, and in particular the conditions applied to the Geelong Star,

are extremely strict. Clearly, they are designed

to provide a high degree of public

confidence that the operations of the vessel are being closely monitored and

managed.49

1.54 Seafish Tasmania concluded:

The company has made substantial

investments in supporting scientific surveys and more recently in bringing

freezer trawlers from Europe to catch our quota and to produce high quality

fish for human consumption. It is time to let us get on with the job of

catching our quota.50

1.55 Seafish Tasmania and the Small

Pelagic Fishery Industry Association (SPFIA) also argued that the science-based

management of the fishery and the statutory fishing rights associated with the

vessel should be respected. For example, the SPFIA submitted:

The impact of the continued political

interventions in the management of the Small Pelagic Fishery is being felt well

beyond the confines of this Association. Although SPF quota holders are

effectively the primary target of the political attacks, there is widespread

erosion of industry confidence in the ability of AFMA to manage fisheries in an

independent, non-political and science based manner. Consequently, industry

confidence in the quality and security of their Statutory Fishing Rights is

being steadily undermined.

In these destabilising circumstances,

it should not be surprising if industry were to take a shorter term view of

their investments reflecting the increased political risk being faced. This is

exactly the situation that Government sought to avoid by providing the fishing

industry with well defined, long term secure fishing rights to inspire

operators to take economically responsible decisions and to look after the

marine resources on which their businesses depend.51

1.56 Other commercial fishing interests

urged the committee and other interested stakeholders to separate concerns

about factory freezer vessels operating in the SPF, where resource sharing

issues involving recreational fishers are important, and the operation of

factory freezer trawlers in other fisheries. Petuna Sealord Deepwater Fishing,

which has operated a factory freezer vessel in the blue grenadier fishery since

1988, urged the committee to separate 'what we see are two dissimilar issues',

namely concerns about 'super trawlers' in the SPF and the operation of factory

freezer trawlers elsewhere. It explained:

The current community concern which has

led to this inquiry is not necessary driven by the size or freezing capacity of

the vessel or the science of the fishery, as evidenced in the blue grenadier

fishery, but centres around resource sharing and access to a fish species that

recreational fishers consider is a significant driver in maintaining

healthy populations of key recreational species.52……..

1.62 The Geelong Star is

95 metres long and, therefore, is not covered by the 130-metre definition of

super trawler used for the ban. Nevertheless, the Geelong Star has

commonly been referred to as a super trawler, including by the media and state

governments.58 In addition, some of the concerns expressed by

groups that opposed the Margiris have similarly been applied

to the Geelong Star. Some submitters also argued that there is only

a marginal difference in the quota allocated to the Abel Tasman,

which was banned, and vessels such as the Geelong Star that

are not.59 Other submitters, however, maintain that 'there is

no correlation between vessel size and fishing power'.60

1.63 On this issue, Mr Allan Hansard,

Managing Director, Australian Recreational Fishing Foundation, commented: 'It

is not necessarily the size of the boat; it is that intensity that we need to

really focus on in this case'.61

1.64 From the perspective of the Stop

the Trawler Alliance, which is an alliance of environment, fishing and tourism

organisations established in 2012 in response to the Margiris, the

principal issue is that a factory freezer vessel is operating in the SPF, not

that a vessel of a certain size is operating.62......

The end result was this:

Recommendation 1

6.22 The committee recommends that the

Australian government ban all factory freezer mid-water trawlers from operating

in the Commonwealth Small Pelagic Fishery.

The full

report can be read here.

Because the recommendation is not yet reflected in legislation and because there is some uncertainty about the reasons the trawler vacated Australian waters as well as a fear it may eventually return, concerned people should write to Deputy Prime

Minister, Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources, Barnaby Joyce MP and Assistant

Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources, Senator Anne Ruston who have portfolio responsibility for fisheries management and to their federal MP calling on government to permanently ban all freezer mid-water trawlers from operating in Australian Small Pelagic Fisheries.

Friday 25 November 2016

The fate of Australia's dugongs and sea turtles

The fate of Australia’s dugongs and sea turtles due to declining numbers, loss of habitat, pollution, unmonitored legal hunting and illegal poaching is once more being debated in the media.

Traditional hunting advocates say the practise represents a small component of the issues facing sea turtles and dugongs.

Pic: David Reid

Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion has defended traditional hunting at a graduation ceremony for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rangers in Cairns.

Native title laws allow traditional owners to hunt endangered turtles and dugongs.

Wildlife identity Bob Irwin has recently called for a moratorium on current practices but Mr Scullion says hunting isn’t the problem.

“There is evidence to demonstrate it is sustainable and there is no evidence to demonstrate it isn’t,” he says.

“Yes, there are some threats to dugongs and turtles. But none of them come from the ocean, they all come from the land and they’re all associated with degradation of habitat.”

Indigenous ranger Mick Hale runs a turtle hospital, Yuku-Baja-Muliku, with his wife, Larissa, at Archer Point more than 300 kilometres north of Cairns.

“We started about six years ago,” Mr Hale says. “It came about around the time Cyclone Larry and Cyclone Yasi decimated our seagrass beds.

“We noticed a lot of sick turtles around [with no food], so instead of letting them die we started a turtle hospital.

Traditional hunting can be sustainable, Mr Hale says.

“The biggest challenge for us is getting the public to understand that traditional hunting is the smallest percentage of mortality for turtles and dugongs,” he says.

“We’ve got environmental impacts, habitat destruction, global climate change.

“These are all massive contributors to the demise of turtle and dugong populations.”

The Hales are currently caring for three turtles - two green sea turtles and a hawksbill.

“We just do it because it’s what we do,” Ms Hale says. “We look after country and after people so that we do have a sustainable future.”

Injinoo ranger Cristo Lifu says rescuing five olive ridley sea turtles from ghost nets with fellow Cape York rangers recently was a powerful experience.

“They were stranded and stuck in a net,” Mr Lifu says.

“We rescued them but it was lucky we were there. Because if not, they would have been dead in another two or three days.

“It’s just about caring for country. Our elders looked after country before us and it’s our time now to take over.”……

The Australian, 11 November 2016:

…three federal ministers commit to talk to indigenous rangers and the Queensland state government to spearhead moves that could see more “no take’’ zones introduced in a bid to stop the vulnerable species being poached and traded, as revealed in The Australian last month…..

The North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance says commercialisation claims have been found to be “unsubstantiated”, while environmental groups point out that dugongs and turtles face far greater threats than hunting, including loss of habitat, marine debris and coastal development.

The Cairns Post, 9 August 2016:

AN indigenous leader claims a moratorium on dugong and turtle hunting will not work and will only push poachers further underground.

The Coalition is preparing draft legislation to provide stronger protection for the marine creatures from over-exploitation by traditional owner groups.

Leichhardt MP Warren Entsch has said he is not happy with some elements of the draft legislation and wants a blanket moratorium on the traditional take of the species.

Girringun Aboriginal Corporation chief executive Phil Rist said his group’s TUMRA (Traditional Use of Marine Resource Agreement) had ensured populations of turtles and dugongs along the Cassowary Coast remained sustainable for 10 years.

He said imposing a moratorium on hunting of the animals would push illegal hunting and exploitation further underground.

“TUMRAs around turtles and dugongs are the way to go,” he said.

“These are instruments for us – ourselves – to better manage our take of turtle and dugong on a sustainable level.

“These agreements are endorsed by the State and Federal governments, and we have proven that they work and they work really well.”

Cairns Turtle Rehabilitation Centre co-ordinator Jennie Gilbert supported a moratorium on turtle hunting, saying the animals definitely needed more protection in Far Northern waters.

“They have got enough threats in their lives without hunting,” she said. “We know that there’s illegal hunting and poaching going on out there.

“The numbers of green sea turtles in Far North Queensland still haven’t recovered from the mass stranding event of 2012, due to a lack of feeding grounds.”

BACKGROUND

ABC News, 27 September 2014:

The Federal Government is warning anyone involved in the illegal trade of dugong and turtle meat that they will be caught.

The Government has allocated $5 million to a dugong and turtle protection plan that involves the Australian Federal Police (AFP), Customs and Border Protection, and the Australian Crime Commission.

Environment Minister Greg Hunt said the Crime Commission has been given $2 million to investigate the illegal trade.

Traditional owners have given their backing to the Government's protection plan.

"They know that their good name is being used by poachers," Mr Hunt said.

"We are determined to end the illegal trafficking in dugong and turtle meat and to protect these majestic creatures."

Under the Native Title Act of 1993, Indigenous people with native title rights can hunt marine turtles and dugong for personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs, and "in exercise and enjoyment of their native title rights and interests".

Dugong and turtle poaching has been identified as a problem in the Northern Territory and Queensland, where the animals are hunted and the meat sold illegally.

National Indigenous radio broadcaster Seith Fourmile said non-Indigenous people were also involved in the illegal trade.

"They are involved with the trading, with selling it, passing it down - some of the turtle meat has gone as far south as Sydney and Melbourne," he said.

Australian Government Dugong and Turtle Protection Plan 2014-2017:

To enhance the protection of our iconic marine turtles and dugong in Far North Queensland and the Torres Strait, the Australian Government has committed $5.3 million over three years for delivery of a Dugong and Turtle Protection Plan under the Reef 2050 Plan and Reef Trust. The plan addresses threatening processes that impact on the long-term recovery and survival of these protected migratory species. Information about the Reef 2050 Plan and Reef Trust is available at www.environment.gov.au/marine/gbr/reef-trust

The Dugong and Turtle Protection Plan includes the following seven core elements:

1. $2 million for a Specialised Indigenous Ranger Programme for strengthened enforcement and compliance and marine conservation in Queensland and the Torres Strait

The programme is being delivered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. More information is available at www.indigenous.gov.au/news-and-media/announcements/minister-scullion-2-million-strengthen-compliance-powers-indigenous

The programme is being delivered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. More information is available at www.indigenous.gov.au/news-and-media/announcements/minister-scullion-2-million-strengthen-compliance-powers-indigenous

2. $2 million for an Australian Crime Commission investigation into the illegal poaching, transportation and trade of turtle and dugong meat in the Great Barrier Reef and Torres Strait

A fact sheet about the investigation by the commission’s Wildlife and Environmental Crime Team is available at

https://www.crimecommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/ Wildlife%20%26%20Environmental%20Crime%20Team%20FACTSHEET%20281114.pdf(link is external)

A fact sheet about the investigation by the commission’s Wildlife and Environmental Crime Team is available at

https://www.crimecommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/ Wildlife%20%26%20Environmental%20Crime%20Team%20FACTSHEET%20281114.pdf(link is external)

3. $700 000 for marine debris clean-up initiatives

Information about the Great Barrier Reef marine debris clean-up initiative is available at www.environment.gov.au/minister/hunt/2014/mr20141113a.html

Information about the Great Barrier Reef marine debris clean-up initiative is available at www.environment.gov.au/minister/hunt/2014/mr20141113a.html

4. $600 000 to support the Cairns and Fitzroy Island Turtle Rehabilitation Centre

The Reef Trust will support the work of the centre to rehabilitate sick and injured turtles and return them to the marine environment.

Information about the Cairns and Fitzroy Turtle Rehabilitation Centre is available at www.saveourseaturtles.com.au/about-ctrc.html(link is external) and www.fitzroyisland.com/newsroom/meet-patients-cairns-turtle-rehabilitation-centre(link is external)

The Reef Trust will support the work of the centre to rehabilitate sick and injured turtles and return them to the marine environment.

Information about the Cairns and Fitzroy Turtle Rehabilitation Centre is available at www.saveourseaturtles.com.au/about-ctrc.html(link is external) and www.fitzroyisland.com/newsroom/meet-patients-cairns-turtle-rehabilitation-centre(link is external)

5. Working with Indigenous leaders to provide for traditional use and reef protection

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority is working with Traditional Owners to develop Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreements to provide for traditional use and deliver reef protection. This may also include voluntary no take agreements.

Information about the agreements is available at www.gbrmpa.gov.au/our-partners/traditional-owners/traditional-use-of-marine-resources-agreements(link is external)

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority is working with Traditional Owners to develop Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreements to provide for traditional use and deliver reef protection. This may also include voluntary no take agreements.

Information about the agreements is available at www.gbrmpa.gov.au/our-partners/traditional-owners/traditional-use-of-marine-resources-agreements(link is external)

6. Federal legislation tripling the penalties for poaching and illegal transportation of turtle and dugong meat

The Environment Legislation Amendment Act 2015 amends various sections of the EPBC Act and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 (Marine Park Act) to provide additional protection for turtles and dugong. The amendments triple the maximum penalties for various criminal offences related to the killing, injuring, taking, trading, keeping or moving of turtles and dugong under the EPBC Act and for criminal offences and civil penalty provisions which apply to the taking of, or injury to, turtles and dugong where they are a protected species under the Marine Park Act.

The tripling of maximum penalties does not impact on the rights of Native Title holders under the Native Title Act 1993 to hunt turtle and dugong for personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs.

Information about the legislation is available at www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/ Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5128

The Environment Legislation Amendment Act 2015 amends various sections of the EPBC Act and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 (Marine Park Act) to provide additional protection for turtles and dugong. The amendments triple the maximum penalties for various criminal offences related to the killing, injuring, taking, trading, keeping or moving of turtles and dugong under the EPBC Act and for criminal offences and civil penalty provisions which apply to the taking of, or injury to, turtles and dugong where they are a protected species under the Marine Park Act.

The tripling of maximum penalties does not impact on the rights of Native Title holders under the Native Title Act 1993 to hunt turtle and dugong for personal, domestic or non-commercial communal needs.

Information about the legislation is available at www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/ Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5128

7. A national approach to dugong and turtle management

Refers to the nationally co-ordinated management of turtle and dugong in Australia. This includes the development of EPBC Act policy documents and guidelines such as updating the Recovery Plan for Marine Turtles of Australia 2003, Marine Turtle Referral Guidelines and policy guidelines for dugong and seagrass habitats.

Refers to the nationally co-ordinated management of turtle and dugong in Australia. This includes the development of EPBC Act policy documents and guidelines such as updating the Recovery Plan for Marine Turtles of Australia 2003, Marine Turtle Referral Guidelines and policy guidelines for dugong and seagrass habitats.

Sunday 20 November 2016

This is just not good enough, Premier Baird!

This lack of prior consultation with indigenous Native Title holders or registered claimants happens too often at state and local government level in NSW to be considered instances of accidental oversight.

It certainly does not show the NSW Government in a good light when it ignores both federal and state legislation and/or regulations requiring such consultation.

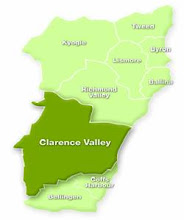

Click on image to enlarge

Sunday 6 November 2016

At the Meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in Hobart Australia it was unanimously agreed to create Ross Sea marine protected area

Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, media release, 28 October 2016:

CCAMLR to create world's largest Marine Protected Area

The world's experts on Antarctic marine conservation have agreed to establish a marine protected area (MPA) in Antarctica's Ross Sea.

This week at the Meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in Hobart, Australia, all Member countries have agreed to a joint USA/New Zealand proposal to establish a 1.55 million km2area of the Ross Sea with special protection from human activities.

This new MPA, to come into force in December 2017, will limit, or entirely prohibit, certain activities in order to meet specific conservation, habitat protection, ecosystem monitoring and fisheries management objectives. Seventy-two percent of the MPA will be a 'no-take' zone, which forbids all fishing, while other sections will permit some harvesting of fish and krill for scientific research.

CCAMLR Executive Secretary, Andrew Wright, is excited by this achievement and acknowledges that the decision has been several years in the making.

"This has been an incredibly complex negotiation which has required a number of Member countries bringing their hopes and concerns to the table at six annual CCAMLR meetings as well as at intersessional workshops.

"A number of details regarding the MPA are yet to be finalised but the establishment of the protected zone is in no doubt and we are incredibly proud to have reached this point," said Mr Wright.

CCAMLR's Scientific Committee first endorsed the scientific basis for proposals for the Ross Sea region put forward by the USA and New Zealand in 2011. It invited the Commission to consider the proposals and provide guidance on how they could be progressed. Each year from 2012 to 2015 the proposal was refined in terms of the scientific data to support the proposal as well as the specific details such as exact location of the boundaries of the MPA. Details of implementation of the MPA will be negotiated through the development of a specific monitoring and assessment plan. The delegations of New Zealand and the USA will facilitate this process.

This year's decision to establish a Ross Sea MPA follows CCAMLR's establishment, in 2009, of the world’s first high-seas MPA, the South Orkney Islands southern shelf MPA, a region covering 94 000 km2 in the south Atlantic.

"This decision represents an almost unprecedented level of international cooperation regarding a large marine ecosystem comprising important benthic and pelagic habitats," said Mr Wright.

"It has been well worth the wait because there is now agreement among all Members that this is the right thing to do and they will all work towards the MPA's successful implementation," he said.

MPAs aim to provide protection to marine species, biodiversity, habitat, foraging and nursery areas, as well as to preserve historical and cultural sites. MPAs can assist in rebuilding fish stocks, supporting ecosystem processes, monitoring ecosystem change and sustaining biological diversity.

Areas closed to fishing, or in which fishing activities are restricted, can be used by scientists to compare with areas that are open to fishing. This enables scientists to research the relative impacts of fishing and other changes, such as those arising from climate change. This can help our understanding of the range of variables affecting the overall status and health of marine ecosystems.

ABC News, 28 October 2016:

A hard-won agreement to establish the first large-scale marine park in international waters south of Australia has been described as a "turning point" for conservation, however an expiry date of 35 years concerns the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Today, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) meeting in Hobart announced agreement had been reached between the member nations over the establishment of the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, which will cover more than one and a half million square kilometres in Antarctica.

The agreement follows years of wrangling and failure to reach consensus, with Russia proving to be a stumbling block.

The area, which has been described as "the size of France, Germany and Spain combined", is revered for its biodiversity.

"Today's agreement is a turning point for the protection of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean," Chris Johnson, WWF Australia Ocean Science Manager, said.

"It is home to one third of the world's Adélie penguins, one quarter of all emperor penguins, one third of all Antarctic petrels, and over half of all South Pacific Weddell seals."

Mr Johnson said while the announcement was "good news", the expiration of the zone after 35 years was a cause for concern…..

Friday 4 November 2016

Australia and New Zealand successful in gaining IWC review of process by which 'scientific' slaughter of Antarctic whales is allowed to continue

On 28 October 2016 the International Whaling Commission (IWC) considered a draft resolution by Australia and New Zealand seeking to improve the review process for whaling under special permit.

Special permits being the mechanism used by the Government of Japan to continue its annual slaughter of whales in the Southern Ocean for the commercial benefit of a domestic niche market for whale meat for human consumption and for the Japanese pet food industry.

The resolution was passed.

IWC, 27 October 2016:

Governments on all sides

of the scientific whaling debate highlighted the positive and constructive

spirit of negotiations on a Resolution

on Improving the Review Process for Whaling under Special Permit, but

ultimately agreement could not be reached and the Resolution was put to a vote

which adopted the Resolution with 34 yes votes, 17 no votes and 10

abstentions. Amongst the measures included is the establishment of a

new Commission Working Group to consider Scientific Committee reports and

recommendations on this issue.

Excerpt from the final version of Resolution 2016-2 - Resolution on Improving the Review Process for Whaling under Special Permit:

“Now, therefore the Commission:

1. Agrees to establish a Standing Working Group (“the Working Group”), in accordance with Article III.4 of the Convention. The Working Group will be appointed by the Bureau on the basis of nominations from Contracting Governments, to consider the reports and recommendations of the Scientific Committee with respect to all new, ongoing and completed special permit programmes and report to the Commission, in accordance with the Terms of Reference contained in the Appendix to this resolution.

2. Agrees that the discussion of special permit programmes be afforded sufficient priority and time allocation to allow for adequate review at both Commission and Scientific Committee meetings;

3. In order to facilitate the Commission’s timely and meaningful consideration of new, ongoing and completed special permit programmes, Requests Contracting Governments to submit proposals for new special permit programmes, and review documentation for ongoing and completed special permit programmes, at least six months before the Scientific Committee meeting held in the same year as a Commission meeting (see the indicative process set out in paragraph 9 of the Appendix);

4. In order to facilitate the Scientific Committee’s review of new, ongoing and completed special permit programmes, Requests Contracting Governments to provide members of the Scientific Committee unrestricted and continuing access to all data collected under special permit programmes that are:

a. used in the development of new programmes; or

b. included in ongoing or final programme reviews. Data made available in accordance with this request shall be used only for the purposes of evaluation and review of special permit programmes.

5. Instructs the Scientific Committee to inform the Commission as to whether Scientific Committee members had unrestricted and continuing access to data collected under special permit programmes, and analyses thereof;

6. Further instructs the Scientific Committee to provide its evaluation of proposals to the Commission in the same year as a Commission meeting (regardless of when the Scientific Committee’s review commences), and to make necessary revisions to its procedures for reviewing special permit programmes, including Annex P, to incorporate the expectation that Contracting Governments will schedule any special permit programmes in accordance with the process outlined in paragraph 3;

7. Agrees that the Commission will consider the reports of the Scientific Committee and of the Working Group at the first Commission meeting after the Scientific Committee has reviewed the new, ongoing or completed special permit programme in question and, taking into account those reports, the Commission will: a. form its own view regarding:

i. whether the review process has adequately followed the instructions set out in Annex P and any additional instructions provided by the Commission ;

ii. whether the elements of a proposed special permit programme, or the results reported from an ongoing or completed special permit programme, have been adequately demonstrated to meet the criteria set out in the relevant terms of reference in Annex P, and any additional criteria elaborated by the Commission; and

iii. any other relevant aspect of the new, ongoing or completed special permit programme and review in question;

b. provide any recommendations or advice it considers appropriate to the responsible Contracting Government regarding any aspect of the new, ongoing or completed special permit programme, including affirming or modifying any proposed recommendations or advice proposed by the Scientific Committee.

c. provide any direction it considers appropriate to the Scientific Committee.

d. make public a summary of the Commission’s conclusions in this respect, by way of publication on the Commission’s website, within 7 days of the end of the Commission meeting.”

Background

The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 March 2016:

Tokyo: Japan's whaling fleet returned on Thursday from its Antarctic hunt after a year-long suspension with a take of more than 300 whales, including pregnant females.

The International Court of Justice ruled in 2014 that Japan's whaling in the Southern Ocean should stop, prompting it to call off its hunt that season, although it said at the time it intended to resume later.

Japan then amended its plan for the next season to cut the number of minke whales it aimed to take by two-thirds from previous hunts.

Its fleet set out in December despite international criticism, including from important ally the United States.

The final ships of the four-vessel whaling fleet returned to Shimonoseki in southwestern Japan on Thursday, having achieved the goal of 333 minke whales, the Fisheries Agency said.

Of these, 103 were males and 230 were females, with 90 per cent of the mature females pregnant.

Friday 21 October 2016

Say No To Shark Nets and watch turtle release at Lighthouse Beach, Ballina at 10am Sunday 23 October 2016

Shark nets are not the answer.

Fundamentally shark nets don't keep people safe and 80% of what they kill will be harmless to humans.

Proponents of shark nets will tell you that there have been no shark attacks at a netted beach in NSW since 1937. Wrong.

NSW Dept of Primary Industries report 27 attacks including one fatality at netted beaches.

Assoc Prof Laurie Laurenson of Deakin University studied 50 years of data from shark mitigation programs (culling and netting). He found no statistical difference in the rate of shark attack and the density of sharks in an area.

The only shark mitigation measure in the world that has proven to be 100% effective is the Shark Spotters program in Cape Town, South Africa. Eleven years and not a single attack, in a very popular beach area with an abundance of White Sharks.

Shark attack is an incredibly rare event. 6 people in a year across the entire planet died from sharks in 2015. Almost everything else you can think of kills more people. More people died taking selfies.

Over the years, I've done a fair number of media interviews. But I have experienced nothing even remotely close to the media feeding frenzy that follows a shark attack.

I was there the day Cooper Allen was bitten a few weeks ago. Even as he was carried down the beach toward the surf club it was clear he would be OK. But still, within an hour, every major news outlet in the country was on the beach, posting hourly updates, gathering enough footage to lead the evening news bulletin. Totally out of proportion to what had actually just occurred.

There is no doubt our community is spooked. There is a genuine fear among our surfers. I regularly hear, "but something must be done". I agree.

We cannot ignore the impact on our community, on the town's reputation, on our tourism and hospitality industries which contribute so much to our local economy.

But we need to look at what hasn't been done yet and what might actually work.

Surf clubs have applied for funding for watch towers. A basic that has still not been funded.

A trial of paid professional shark spotters at Byron Bay was discontinued after no ongoing funding.

The Shark Watch group formed locally with no assistance from Council or the State Government. Specifically designed to keep watch on our surfers from headlands using volunteers and drones, the group is still waiting to hear on a funding application for $50,000 to provide equipment and training.

A trial of paid professional shark spotters at Byron Bay was discontinued after no ongoing funding.

The Shark Watch group formed locally with no assistance from Council or the State Government. Specifically designed to keep watch on our surfers from headlands using volunteers and drones, the group is still waiting to hear on a funding application for $50,000 to provide equipment and training.

Where are the shark alarms we were promised?

Where are the shark bite first aid kits?

Why do we have a funding program for innovative responses, but the one company that has developed an effective deterrent, Shark Shield, is getting no assistance from government to get their product to market?

Where are the shark bite first aid kits?

Why do we have a funding program for innovative responses, but the one company that has developed an effective deterrent, Shark Shield, is getting no assistance from government to get their product to market?

All of these things are far more effective in preventing shark attack than nets. But still we wait.

Shark nets are a fishing device, not a barrier. The nets in NSW are 150m long, 6m high and are placed in water 10-12m deep. As a fishing device they

have the highest by-catch rate of any technique available.

I've spent the last 9 years of my life trying to protect and save our local sea turtle population through Australian Seabird Rescue. All species of sea turtle are at risk of extinction. Everything I've done will be wasted if we introduce shark nets. Quite simply the nets will kill more turtles than we have been able to save.

The 60 bottlenose dolphins that make up the Richmond River pod face decimation, with DPI staff estimating that up to 20 could be killed in the first few months of shark nets.

These are some of the reasons why I'll be joining my colleagues from Seabird Rescue at Lighthouse Beach at 10am this Sunday (23/10).

We'll be releasing Kimba the green sea turtle after 3 months in care. Back to the ocean, where the sharks also live. But the greatest threat to Kimba isn't sharks. It's humans.

Please join us in saying no to shark nets.

* Image from Facebook

Labels:

Ballina,

environment,

marine life,

oceans,

protected species

Sunday 16 October 2016

Not impressed by the arguments made for shark netting the NSW Far North Coast

The following article was one of the more balanced media reports on shark attacks on the NSW North Coast since the fatality at Ballina in 2015.

A fatality which brought shark attack deaths in the region to seven in thirty-four years – that is, an average of one fatality every 4.85 years.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 October 2016:

The Baird government's decision to drop its opposition to shark nets for the state's northern beaches ignored recommendations of one of its own departments and the scientific consensus, experts say.

Another shark bite last week – the sixth since the start of 2015 for the Ballina-Byron area alone – was the last straw for Premier Mike Baird. On Wednesday, he explained his backflip, saying it was time to "prioritise human life over everything".

Only one fatality has been recorded in the state's 51 netted beaches since their introduction in Sydney in 1937, back in 1951. There have, though, been 33 so-called unprovoked attacks some serious ones.

"We need some sort of protection," said Richard Beckers, owner of Ballina Surf shop and a supporter of the nets.

Mr Beckers said he had cancelled $100,000 in orders after two incidents in as many weeks. Sales of body and surf boards have dived about 90 per cent as surfers head to beaches considered safer elsewhere….

Until last week, Mr Baird – himself a keen surfer – had resisted calls for the nets. Instead, he heeded advice from scientists who argue there is little evidence nets alone make beaches safer while killing thousands of marine creatures over the years.

The policy reversal "is a political decision – it's not based on data," said Culum Brown, an associate professor at Macquarie University. "The costs are well known and there's little to nothing in terms of benefits."

Existing nets are typically 150 metres long and about six metres deep, allowing plenty of space for sharks to get around, over or under them.

A parliamentary inquiry earlier this year recommended the Department of Primary Industries "move toward replacement of current shark meshing with more ecologically sustainable technologies".

Colin Simpfendorfer, director of the Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture at James Cook University, said great white sharks have been protected for two decades in a bid to reverse their population's steep decline.

"The whole point [of nets] is that they catch sharks," Professor Simpfendorfer said. "You are looking to reduce the abundance of sharks where people want to swim."

The 189 sea creatures caught in the existing nets in 2014-15 included 44 target sharks – whites, tigers and bulls – as well as harmless shark species, dolphins and turtles. Of these, 116 died before they could be released, government data shows.

Over the past century, the national annual deaths from sharks is 1.3 people on average, rising to two people during the past five years, according to Taronga Zoo's shark file. Australians make an estimated 100 million visits to the beach a year.

By contrast, five people died from dogs in 2013, with 44 killed by falling out of bed, the Australian Bureau of Statistics said.

"You're more likely to get killed by bees or by horses than by sharks," Professor Brown said.

Of course the NSW Coalition Government, and particularly Premier Mike Baird furiously chasing electoral popularity in the face of falling poll numbers, is not inclined to step back from the recent back flip on shark netting.

Readers can make up their own minds about whether trying to lay shark netting on the NSW Far North Coast in the face of an increasingly warm and fast Australian Eastern Current and frequently gale-driven coastal seas is going to work.

The Baird Government's $16 million attempt earlier this year to install shark netting at Lighthouse Beach, Ballina and Seven Mile Beach, Lennox Head failed miserably due to predictable rough conditions, large swells and sand movement along the coast.

Below are excerpts from Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters (2011) by John G. West Coordinator, Australian Shark Attack File, Taronga Conservation Society Australia.

The Baird Government's $16 million attempt earlier this year to install shark netting at Lighthouse Beach, Ballina and Seven Mile Beach, Lennox Head failed miserably due to predictable rough conditions, large swells and sand movement along the coast.

Below are excerpts from Changing patterns of shark attacks in Australian waters (2011) by John G. West Coordinator, Australian Shark Attack File, Taronga Conservation Society Australia.

ABSTRACT. Although infrequent, shark attacks attract a high level of public and media interest, and often have serious consequences for those attacked.

Data from the Australian Shark Attack File were examined to determine trends in unprovoked shark attacks since 1900, particularly over the past two decades.

The way people use the ocean has changed over time. The rise in Australian shark attacks, from an average of 6.5 incidents per year in 1990–2000, to 15 incidents per year over the past decade, coincides with an increasing human population, more people visiting beaches, a rise in the popularity of water-based fitness and recreational activities and people accessing previously isolated coastal areas.

There is no evidence of increasing shark numbers that would influence the rise of attacks in Australian waters. The risk of a fatality from shark attack in Australia remains low, with an average of 1.1 fatalities year1 over the past 20 years.

The increase in shark attacks over the past two decades is consistent with international statistics of shark attacks increasing annually because of the greater numbers of people in the water.

RESULTS

Over the 218 years for which records were available, there have been 592 recorded unprovoked incidents in Australian waters, comprising 178 fatalities, 322 injuries and 92 incidents where no injury occurred.

Most of these attacks have occurred since 1900, with 540 recorded unprovoked attacks, including 153 fatalities, 302 injuries and 85 incidents where no injury occurred.

Attacks have occurred around most of the Australian coast, most frequently on the more densely populated eastern coast and near major cities (Fig. 1).

In the first half of the 20th century, there was an increase in the number of recorded shark attacks, culminating in a peak in the 1930s when there were 74 incidents (Fig. 2).

The number of attacks then dropped, to stabilise ,35 incidents per decade from the 1940s to the 1970s. Since 1980, the number of reported attacks has increased to 121 incidents in the past decade (Fig. 2).

There had been a decrease in the average annual fatality rate, which had fallen from a peak of 3.4 year1 in the 1930s, to an average of 1.1 year1 for the past two decades.

The number of fatal attacks relative to the number of total attacks per decade has also decreased over this period, from 45% in the 1930s to 10% in the past decade. These declining chances of a shark attack resulting in fatality are also reported elsewhere in the world (Woolgar et al. 2001; Burgess 2009).

In the 20-year period of the 1930s and 1940s, the fatality ratio was 1:2.4 incidents. In the past 20 years, the fatality ratio has been 1:8.5 incidents.

Comparison of attacks per capita indicated that the number of incidents was highest in the 1930s, at 10 attacks per million people per decade, decreasing to an average of 3.3 attacks per million people per decade until the 1990s.

The past two decades have exhibited an increase in attacks, up to 3.5 attacks per million people per decade (1990–1999) and 5.4 attacks per million people per decade 2000–2009 (Fig. 3).

In the 20 years since 1990, there have been 186 reported incidents, including 22 fatalities (Table 1).

This represents a 16% increase in reported attacks during 1990–1999 and a 25% increase over the past 10 years (Fig. 3).

The majority of attacks occurred in New South Wales (NSW) with 73 incidents (39%), then Queensland with 43 incidents (23%), Western Australia (WA) with 35 incidents (19%), South Australia with 20 incidents (11%), Victoria with 12 incidents (6%), Tasmania with two incidents (1.5%) and Northern Territory with one incident (0.5%)

CONCLUSION

Patterns of attack have changed substantially over time as a result of the changing population and human behaviour.

If human activity related to water-based activities and the use of beaches, harbours and rivers continues to change, we can expect to see further changes in the patterns, distribution, frequency and types of attacks in the future.

Encounters with sharks, although a rare event, will continue to occur if humans continue to enter the ocean professionally or for recreational pursuit.

It is important to keep the risk of a shark attack in perspective. On average, 87 people drown at Australian beaches each year (SLSA 2010), yet there have been, on average, only 1.1 fatalities per year from shark attack over the past two decades.

It is clear that the risk of being bitten or dying from an unprovoked shark attack in Australia remains extremely low.

According to Taronga Conservation Society there have been 216 recorded unprovoked shark attacks in New South Wales in the last 100 years of which 48 were fatal.

UPDATE

The unintended impacts of shark mesh was on show on Saturday, with a juvenile humpback whale becoming entangled in a net near Coolangatta on the Gold Coast. The calf's mother helped keep the animal near the surface long enough for a patrol to arrive and cut the whale free. [The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 October 2016]

in 1951, New South Wales recorded its worst year of shark encounters at netted beaches, with three separate incidents, including the fatality of local surf ski champion Frank Olkulich (21) who was fatality bitten at a Newcastle Beach called Merewether while treading water……In the 23 years, since September 1992, there has been 21 unwanted shark encounters at netted beaches in NSW; almost one per year*. This doesn’t include the death of a 15-year old boy who drowned after being caught in a shark net at Shoal Bay in March 2007.[3] It does however include the shark incident on 12 February 2009 at Bondi Beach when Glen Orgias (33) lost his left hand after being bitten by a 2.5m white shark while surfing and the severe bite that Andrew Lindop (15) received by a suspected 2.6m white shark at Avalon Beach on 1 March 2009……In January 2012, surfer Glen Folkard was severely bitten by a bull shark at Redhead Beach, north of Sydney. This incident is still waiting a review by DPI, New South Wales, and, along with another two unwanted shark encounters at meshed beaches, was meant to be part of the programme’s 5-year review in September 2014. At the time of this article, this review has still not been finalised. [Sea Shepherd, 5 August 2015]

Labels:

marine life,

NSW North Coast,

protected species,

safety,

sharks

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)