Thursday, 8 March 2018

Australian workplaces still hostile territory for women

“When asked

about a range of job attributes, women placed most value on having a job where

they would be treated with respect (80%), where their job was secure (80%),

where the job paid well (65%), was interesting (64%) and offered the

flexibility they might need (62%). The majority of women viewed their job as

being useful to society (69%) and felt that their job allowed them to ‘help

others’ (73%). Two in five working women (43%) said they felt stressed at work,

with it more likely being an issue for younger women, those still in education,

and those in lower paid or casual roles. One in five women (20%) said they felt

isolated at work, particularly those self-employed and working at home.

Two-thirds of women said they received paid sick (67%) and annual leave (65%).

Fewer received paid parental leave (42%) and paid carers leave (43%), and one

in five women were unaware whether or not they received these entitlements at

work.”

[Marian Baird et al, 2018, Women and the Future of Work: Report1of The Australian Women’s Working

Futures Project, p.4]

University of

Sydney, News and Opinion, Significant

gaps between working women's career goals and reality, 6 March 2018:

First study to examine

women and future of work

Australian workplaces

are not ready to meet young women's career aspirations or support their future

success, according to a new national report by University of Sydney

researchers.

“We are talking more

about robots than we are about women in the future of work debate – this must

change,” said co-author of the report, Professor

Rae Cooper.

Launched today,

the Women and the Future of Work report reveals the gaps

and traps between young working women’s aspirations and their current working

realities.

“There are significant

gaps in job security, respect, access to flexibility and training,” said Dr Elizabeth Hill, co-author of the report.

“Government, businesses

and industry need to step up and take action so that our highly educated and

highly skilled young women are central to the future of work.”

The team of researchers

from the University of Sydney’s Women, Work &

Leadership Research Group, surveyed more than 2000 working women aged 16 to

40, who were representative of the workforce nationally.

The report is the first

of its kind and found that young women were generally not concerned about job

loss as a result of automation and economic change.

“Almost two-thirds of

the women we surveyed said they didn’t fear robots coming for their jobs in the

future,” Professor Cooper said.

“Our national debate

about the future of work is too often a hyper-masculinised, metallic version of

work.

“For young women, their

picture of the future workforce is quite different: they see themselves

balancing family and work commitments, and having long, meaningful careers. For

this to be a reality, we need mutually beneficial flexibility in all

workplaces.”

Respect and access to

flexibility critical for women

The survey found being

treated with respect and having job security were critical to ensuring young

women’s future careers.

Despite 90 percent of

women identifying access to flexibility as important, only 16 percent strongly

agreed that they have access to the flexibility they need.

“Young women workers are

generally optimistic about work and ready to contribute,” Dr Hill said. “But

they find themselves caught in gaps between what they need and what the

workforce offers.”

The majority of working

women report that developing the right skills and qualifications is important

for success at work (92 percent). However, only 40 percent said they can access

affordable training to equip them for better jobs.

“Public policy settings,

while improving, remain inadequate,” Dr Hill said. “Projected growth in

feminised, low-paid jobs in health care and social assistance suggests an

urgent need for government action to ensure these jobs meet the criteria of

decent work.

“Current trends toward

fragmentation and the contracting out of employment are undermining many of the

criteria of decent work, making this a pressing policy issue for gender

equality in the future of work,” Dr Hill said.

More women than robots

in future workplaces

The survey also

indicated young women often feel ‘disrespected’ by senior colleagues and

supervisors because of their gender. This was the case both for highly paid

professionals and low‐paid

workers.

Ten percent of

respondents said they were experiencing sexual harassment in their current

workplace. Some groups of women reported higher rates of harassment including:

*

women currently studying (14 percent compared to 8 percent who are not

studying)

*

women living with a disability (18 percent compared to 9 percent not living

with a disability)

*

women born in Asia or culturally and linguistically diverse women (16 percent

compared to 8 percent who are not culturally or linguistically diverse).

“Employers need to

commit and act to create workplaces where women are respected and valued for

their expertise,” Professor Cooper said.

“There will be more

women than robots in the future of work. It’s time that households, government,

businesses and employers listen to them.”

Dr Hill said: “We are

urgently calling on the government to facilitate and implement a public policy

framework that supports young women’s career aspirations.

“We need to work towards

a future where women are valued in the workplace and for their work.”

The study was funded by

the University of Sydney’s Sydney

Research Excellence Initiative 2020. It was authored by the Co-Directors of

the University’s Women, Work & Leadership Research Group, Professor

Marian Baird and Professor Rae Cooper, with Dr Elizabeth Hill, Professor Ariadne Vromen and Professor Elspeth Probyn.

The data collection and

analysis for this research focused on working 16-40 year old Australians, and

was undertaken by Ipsos Australia. It was collected in September-November 2017,

and includes: a nationally representative online survey of 2,100 women; a

survey of 500 men; a booster survey of 50 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

women; and five in-person focus groups of working women.

Full report

can be found here.

“At the time

of study, women with the following characteristics were found as being less

likely to be working (noting that the first of these characteristics may be

age-related):

- Those who have only completed secondary school (70%

compared to 86% of those who have completed tertiary education, for example);

- Those living at home with parents (71% compared to

84% of those living in their own home);

- Women with disability (74% compared with 82% of those

without disability);

- Culturally and Linguistically Diverse women (75% in

comparison to 82% of women who are not Culturally and Linguistically Diverse);

and

- Low-income earners (70% of those earning below

$40,000 as opposed to 88% of those earning above $80,000, for example).”

[Marian Baird et al, 2018, Women and the Future of Work: Report1of The Australian Women’s Working

Futures Project, p.18]

Labels:

access & equity,

inequality,

jobs,

women

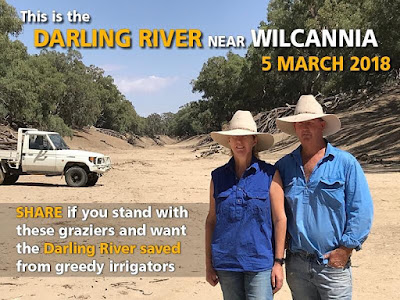

Murray-Darling Basin: water mismanagement just keeps rolling on

Image sourced from Twitter

Having miserably failed to enforce even the most basic of safeguards against widespread water theft in the Murray Darling Basin - such as not allowing unmetered water extraction - the Murray Darling Basin Authority and then water resources minister and now humble Nationals backbencher Barnaby Joyce have left us having to rely on leaks to the media to find out the true state of play in the national water wars.

The

Sydney Morning Herald,

4 March 2018:

The ailing state of the

Darling River has been traced to man-made water extraction, according to a

leaked report by the agency charged with overseeing its health.

The "hydrologic

investigation", dated last November and obtained by Fairfax Media,

analysed more than 2000 low-flow events from 1990-2017 on the

Barwon-Darling River between Mungindi near the NSW-Queensland border down to

Wilcannia in far-western NSW .

The draft report – a

version of which is understood to have been sent to the Turnbull government for

comment – comes days after WaterNSW issued a

red alert for blue-green algae on the Lower Darling River at Pooncarie

and Burtundy.

Bourke

is among towns also on stage-two water restrictions as the Darling

dries up in places

The paper by

Murray-Darling Basin Authority's (MDBA) own scientists found flow behaviour had

changed since 2000, particularly in mid-sections of the river such as between

the towns of Walgett and Brewarrina.

On that section, low or

no-flow periods were "difficult to reconcile with impacts purely caused by

climate", the scientists said.

Indeed, dry periods on

the river downstream from Bourke were "significantly longer than

pre-2000", with the dry spells during the millennium drought continuing

afterwards.

Water resource

development – also described as "anthropogenic impact" – must also

play "a critical role" in the low flows between Walgett and

Brewarrina, the report said.

The revelations

come after

the Senate last month voted to disallow changes to the $13 billion

Murray-Darling Basin Plan that would have cut annual environmental water savings

by 70 billion litres…..

A spokeswoman for the

authority said the report was "undergoing quality assurance processes

prior to publication", with a formal release on its website likely in

coming days.

The MDBA commissioned

the internal team to "address some of the specific concerns raised"

by its own compliance reviews and those of the Berejiklian government, she

said.

Terry Korn, president

of the Australian Floodplain Association, said the report confirmed

what his group's members had known since the O'Farrell government changed the

river's water-sharing plan in 2012 to allow irrigators to pump even during

low-flow periods.

Poor policy had been

compounded by "totally inadequate monitoring and compliance systems",

Mr Korn said.

"Some irrigators

have capitalised on this poor management by the NSW government to such an

extent that their removal of critical low flows has denied downstream

landholders and communities their basic riparian rights to fresh clean

water," he said. "This is totally unacceptable."….

Fairfax Media also

sought comment from federal Agriculture Minister David Littleproud.

Once publicly outed for sitting on the review report the Murray Darling Basin Authority finally decided to publish it this week.

https://www.scribd.com/document/372999806/Murray-Darling-Basn-Compliance-Review-Final-Report-November-2017Once publicly outed for sitting on the review report the Murray Darling Basin Authority finally decided to publish it this week.

The

Sydney Morning Herald,

20 February 2018:

The NSW government

intervened to urge the purchase of water rights from a large irrigator on the

Darling River that delivered a one-off $37 million profit to its owner while

leaving downstream users struggling with stagnant flows.

Gavin Hanlon, the senior

NSW water official who

resigned last September amid multiple inquiries into allegations of

water theft and poor compliance by some large irrigators, wrote to his federal

counterparts in the Agriculture and Water Resources Department, then

headed by Barnaby Joyce, in late December 2016 urging the buyback of water from

Tandou property to proceed.

The Tandou water

purchase proposal "should be progressed...given the high cost of the

alternative water supply solution" for the property south-east of Broken

Hill, Mr Hanlon wrote, according to a document sent on December 23, 2016 and

obtained by Fairfax Media.

Early in 2017, the

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences estimated

the property's annual water entitlements of 21.9 billion litres to be

$24,786,750 "based on recent trade values", according to another

document listed as "Commercial in Confidence".

Despite this valuation,

the federal government by 16 March, 2017 would pay Tandou's owner Webster Ltd

more than $78 million. At its announcement on 21 June last year, Webster said

in a statement it "expects to record a net profit on disposal in the order

of $36-37 million".

The transfer of the

water rights are apparently the subject of inquiries by the NSW Independent

Commission Against Corruption, with several people saying they have discussed

their knowledge of the deal with the agency. An ICAC spokeswoman declined to

comment.

Webster Ltd

styles itself as a leading

Australian agribusiness company with a rich, diverse history spanning over 180

years.

Liberal Party donor Christopher

Darcy “Chris” Corrigan is Executive Chairman and a significant shareholder in this company

Wednesday, 7 March 2018

When it comes to human rights and civil liberties is it ever safe to trust the junkyard dog or its political masters?

On 18 July 2017, Prime

Minister Malcolm Bligh Turnbull announced the establishment of a Home Affairs

portfolio that would comprise immigration, border protection, domestic security

and law enforcement agencies, as well as reforms to the Attorney-General’s

oversight of Australia’s intelligence community and agencies in the Home

Affairs portfolio.

On 7 December 2017, the Prime Minister

introduced the Home Affairs and Integrity Agencies Legislation Amendment Bill2017 into the House of Representatives.

This bill amends the Anti-Money

Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006, the Independent

National Security Legislation Monitor Act 2010, the Inspector-General

of Intelligence and Security Act 1986 and the Intelligence Services Act 2001.

The bill was referred to Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security which tabled its report and recommendations on 26 February 2018.

This new government department on steroids will be headed by millionaire former Queensland Police detective and far-right Liberal MP for Dickson, Peter Craig Dutton.

His 'front man' selling this change is Abbott protégé, former Secretary

of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and current Secretary of the new Department of Home Affairs, Michael Pezzullo.

The question every Australian needs to ask themselves is, can this current federal government, the ministers responsible for and department heads managing this extremely powerful department, be trusted not to dismantle a raft of human and civil rights during the full departmental implementation.

It looks suspiciously as though former Australian attorney-general George Brandis does not think so - he is said to fear political overreach.

The

Saturday Paper,

3-9 March 2018:

On

Friday last week, former attorney-general George Brandis went to see Michael

Pezzullo, the secretary of the new Department of Home Affairs.

The

meeting was a scheduled consultation ahead of Brandis’s departure for London to

take up his post as Australia’s new high commissioner. It was cordial, even

friendly. But what the soon-to-be diplomat Brandis did not tell Pezzullo during

the pre-posting briefing was that he had singled him out in a private farewell

speech he had given to the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation on the

eve of his retirement from parliament two weeks earlier.

As

revealed in The Saturday Paper last week, the then senator Brandis

used the ASIO speech to raise concerns about the power and scope of the new

department and the ambitions of its secretary. Brandis effectively endorsed the

private concerns of some within ASIO that the new security structure could

expose the domestic spy agency to ministerial or bureaucratic pressure.

In

a regular Senate estimates committee hearing this week, Pezzullo described his

meeting with Brandis – on the day before The Saturday Paper article

appeared – as Opposition senators asked him for assurances that ASIO would

retain its statutory independence once it moves from the attorney-general’s

portfolio to become part of Home Affairs.

“I

had a very good discussion on Friday,” Pezzullo told the committee, of his

meeting with Brandis.

“He’s

seeking instructions and guidance on performing the role of high commissioner.

None of those issues came up, so I find that of interest. If he has concerns,

I’m sure that he would himself raise those publicly.”

Labor

senator Murray Watt pressed: “So he raised them with ASIO but not with you?”

“I

don’t know what he raised with ASIO,” Pezzullo responded. “… You should ask the

former attorney-general if he’s willing to state any of those concerns … He’s a

high commissioner now, so he may not choose to edify your question with a

response, but that’s a matter for him. As I said, he didn’t raise any of those

concerns with me when we met on Friday.”

The

Saturday Paper contacted George Brandis but he had no comment.

“ANY

SUGGESTION THAT WE IN THE PORTFOLIO ARE SOMEHOW EMBARKED ON THE SECRET

DECONSTRUCTION OF THE SUPERVISORY CONTROLS WHICH ENVELOP AND CHECK EXECUTIVE

POWER ARE NOTHING MORE THAN FLIGHTS OF CONSPIRATORIAL FANCY…”

Watt

asked Pezzullo for assurance there would be no change to the longstanding

provisions in the ASIO Act that kept the agency under its director-general’s

control and not subject to instruction from the departmental secretary. The

minister representing Home Affairs in the Senate, Communications Minister Mitch

Fifield, said: “It is not proposed that there be a change to that effect.”

The

new Department of Home Affairs takes in Immigration and Border Protection, the

Australian Federal Police, the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, the

Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre, known as AUSTRAC, and ASIO.

ASIO

does not move until legislation is passed to authorise the shift, and will

retain its status as a statutory agency.

Pezzullo

addressed the fears of those questioning his department’s reach. He said some

commentary mischaracterised the arrangements as “being either a layer of overly

bureaucratic oversight of otherwise well-functioning operational arrangements

or, worse, a sinister concentration of executive power that will not be able to

be supervised and checked”.

“Both

of these criticisms are completely wrong,” he said.

Pezzullo

had already described his plans, both to the committee and in a speech he made

in October last year, in which he spoke of exploiting the in-built capabilities

in digital technology to expand Australia’s capacity to detect criminal and

terrorist activity in daily life online and on the so-called “dark web”.

But

the language he used, referring to embedding “the state” invisibly in global

networks “increasingly at super scale and at very high volumes”, left his

audiences uncertain about exactly what he meant.

Watt

asked if there would be increased surveillance of the Australian people. “Any

surveillance of citizens is always strictly done in accordance with the laws

passed by this parliament,” Pezzullo replied.

In

his February 7 speech to ASIO, George Brandis described Pezzullo’s October

remarks as an “urtext”, or blueprint, for a manifesto that would rewrite how

Australia’s security apparatus operates.

Pezzullo

hit back on Monday. “Any suggestion that we in the portfolio are somehow

embarked on the secret deconstruction of the supervisory controls which envelop

and check executive power are nothing more than flights of conspiratorial fancy

that read into all relevant utterances the master blueprint of a new ideology

of undemocratic surveillance and social control,” Pezzullo said.

As for day to day human resources, financial management and transparent accountable governance, media reports are not inspiring confidence in Messrs. Turnbull, Dutton and Pezzullo.

The Canberra Times, 2 March 2018:

The Canberra Times, 2 March 2018:

Home Affairs head Mike

Pezzullo was one of the first to front Senate estimates on Monday.

It's been up and running

for only weeks, but his new department is part of one of the largest government

portfolios.

Having brought

several security agencies into its fold, and if legislation passes letting ASIO

join, the Home Affairs portfolio will be home to 23,000 public

servants.

Mr Pezzullo was also

quizzed on the investigation into Roman Quaedvlieg, the head of

the Australian Border Force who has been on leave since May last year,

following claims he helped his girlfriend - an ABF staff member - get a

job at Sydney Airport.

It was revealed the Prime Minister's department has had a corruption watchdog's

report into abuse of power allegations for at least five months

while Mr Quaedvlieg has been on full pay earning hundreds of thousands of

dollars.

Tuesday, 6 March 2018

Is Australian welfare reform in 2018 a step back into a dark past?

Last year saw the completion of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse which revealed generational abuse within the Australian education and child welfare systems.

That year also revealed the ongoing failure of the Dept. of Human Services and Centrelink to fix its faulty national debt collection scheme, which possibly led to the deaths of up to eleven welfare recipients after they were issued debt advice letters.

The first quarter of 2018 brought a scathing United Nations report on Australia's contemporary human rights record titled Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders on his mission to Australia.

Along with a report into elder abuse in Oakden Older Persons Mental Health Service in South Australia and the release of a detailed Human Rights Watch investigation of 14 prisons in Western Australia and Queensland which revealed the neglect and physical/sexual abuse of prisoners with disabilities, particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme represents yet another crisis. The Productivity Commission has warned there is now no carer of last resort for patients in an emergency, care provider agencies are reportedly owed up to $300 million and disabled people are often receiving inadequate care via untrained staff or sometimes no care at all, as government disability care services are being closed in favour of the new privatised service delivery scheme.

None of these instances stand in isolation and apart from either Australian society generally or government policies more specifically.

They all represent the frequently meagre nature of community compassion and the real level of care governments have been willing to organise and fund for vulnerable citizens. In reality the ideal level of support and care for the vulnerable - that politicians spout assurances about from campaign hustings every three years - is just so much political hot air unless ordinary voters insist that it be otherwise.

As the Turnbull Coalition Government clearly intends to push forward with the full gamut of its punitive welfare reforms perhaps now it the time to consider if we have made any great strides towards a genuinely fair and egalitarian society in the last two hundred years or if we are only dressing up old cruelties in new clothes and calling this "looking after our fellow Australians”, "an exercise in practical love, "an exercise in compassion and in love".

History and Policy, Katie Barclay, Creating

‘cruel’ welfare systems: a historical perspective, 1 March 2018,

excerpts:

Over

the last two decades, commissions and reports on institutional care across the

western world have highlighted widespread physical, sexual, emotional and

economic violence within caring systems, often targeted at society’s most

vulnerable people, not least children, the disabled and the elderly. These have

often come at significant cost not just to the individual, but the nation. As

Maxwell has shown, national apologies, that require the nation to render itself

shamed by such practices, and financial redress to victims, have impacted on

political reputation, trust in state organisations, and finances. As each

report is released and stories of suffering fill newspapers and are quantified

for official redress, both scholars and the public have asked ‘how was this

allowed to happen?’ At the same time, and particularly in the last few years as

many countries have turned towards conservative fiscal policies, newspapers

also highlight the wrongs of current systems.

In

the UK, numerous reports have uncovered abuses within welfare systems, as

people are sanctioned to meet targets, as welfare staff are encouraged to withhold information about services or grants to

reduce demand, and through systematic rejection of first-try benefit applications to

discourage service use. Often excused as ‘isolated incidents’ on investigation,

such accounts are nonetheless increasingly widespread. They are accompanied by

a measurable reduction in investment in welfare and health systems, that have

required a significant withdrawal in services, and have been accompanied with

policies of ‘making work pay’ that have required that benefits be

brought in line, not with need, but with low working incomes. The impact of

these policies and associated staff behaviour have been connected to

increasing child and adult poverty, declining life expectancy, growing homelessness, and the rise in foodbank use.

Importantly,

public commentators on this situation have described this situation as ‘cruel’.

One headline saw a benefits advisor commenting ‘I get brownie points for cruelty’; another noted ‘Welfare reform is not only cruel but chaotic’. The system

depicted in Ken Loach’s I Daniel Blake (2016), described by reviewers

as a Kafka-esque nightmare, a ‘humiliating and spirit-sapping holding pattern of enforced

uselessness’, and a ‘comprehensive [system of] neglect and indifference’, was

confirmed by many as an accurate depiction. Whether or not this representation

of the current welfare system is held to be true, such reporting raises

significant questions about when and how systems designed to provide help and

support move from care to abuse. A focus on ‘isolated incidents’ today can be

compared to the blaming of ‘isolated perpetrators’ in historic cases of abuse,

an account that is now held by scholars to ignore the important role of systems

of welfare in enabling certain types of cruelty to happen…..

The

capacity of welfare systems to support individuals is shaped by cultural

beliefs and political ideologies around the relationship between work, human

nature, and welfare. Here late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Ireland

provides a productive example. Ireland in this period was marked by significant

levels of poverty amongst its lower orders, particularly those that worked in

agriculture. The capacity to manage that poverty on an individual level was

hindered by several economic downturns and harvest failure, that pushed people

to starvation. As a nation without a poor law (welfare) system until 1838, the

poor relied on charity, whether from individuals or institutions for relief. In

the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the ‘state’ (usually local

corporations) introduced more direct welfare, sometimes in the form of relief

payments but more usually access to workhouses.

After 1838 and until the crisis

of the 1847 famine, relief payments were removed and all welfare recipients had

to enter the workhouse. Accompanied by a growth in institutional charitable

services, the success and ‘care’ of the system could vary enormously between

areas and organisations. What it did not do is significantly reduce poverty

levels in the population.

Indeed,

it was important that the poverty levels of welfare recipients were not reduced

by the workhouse system. Like current ‘make work pay’ policies, poverty relief

measures were designed so that those in the workhouse or receiving charity

elsewhere did not have a significantly higher standard of living than those who

provided for themselves. This principle was determined based on the wage of an

independent labourer, one of the poorest but also largest categories of worker.

The problem for the system was that independent labourers earned so poorly that

they barely managed a subsistence diet. Their living conditions were extremely

poor; many slept on hay in darkened huts with little furnishings or personal

property.

Those

who managed the system believed that a generous welfare system would encourage

people to claim benefits and so could potentially bankrupt those paying into

the system. This encouraged an active policy of ‘cruelty’. Not only were

benefit recipients given meagre food and poor living conditions, but families

were routinely broken up, the sexes housed in different wings and prohibited from

seeing each other. Welfare recipients were often ‘badged’ or given uniforms to

mark their ‘shame’, and workhouse labour was designed to be particularly

physically challenging.

It

was a system underpinned by several interlocking beliefs about the Irish, the

value of work and the economy. Hard work was viewed as a moral characteristic,

something to be encouraged from childhood and promoted as ethical behaviour.

Certain groups, notably the Irish poor but also the British lower orders and

non-Europeans more generally, were viewed as lacking this moral characteristic

and required it to be instilled by their social betters. Welfare systems that

were not carefully designed to be ‘less eligible’ (i.e. a harsher experience

than ‘normal; life for the working poor), were understood to indulge an innate

laziness…..

Throughout

history, welfare services have required considerable economic investment.

Unsurprisingly, this has required those who run institutions of care for people

also to keep a careful eye on their financial bottom line. More broadly, it has

also required a monitoring of services to ensure value for money for the state

and its taxpayers and to protect the interests of the service users. As has

been seen recently in discussions of targets placed on staff providing welfare

provision in the UK, such measuring systems can come to shape the nature and

ethos of the service in damaging ways.

A

relevant historical example of this is from the Australian laundry system in

the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Young women were placed in youth

homes and registered as delinquent for a wide range of reasons from petty

criminal behaviour to perceived immorality (ranging from flirting with the

opposite sex to premarital pregnancy), to having been neglected by parents.

These homes, often run by religious organisations, were designed to ‘reform’

young (and occasionally older) women, preventing them from entering

prostitution or other criminal pursuits. The main mechanism for ‘reform’ was through

a moral discipline of work, which in many of these organisations revolved

around a professional laundry service. Work was often unpaid or paid at very

nominal sums, given to women on their release. The service, which catered to

the general public, kept institutions financially afloat, and many became

significant-sized businesses. They required women to work very long hours, in

challenging conditions. Accidents, particularly burns, were not unusual. As

businesses grew, other ‘reform’ efforts that ran alongside, such as education,

became rarer.

The

laundry became the driving focus of the institution. The women were cheap

labour, and managing that machine became not just a means to an end, but shaped

the logic and functioning of the care service. It is an example of how an

economic imperative can come to adversely impact on care, by disrupting the

purposes and functions of the service. It was also a process that significantly

reduced the level of ‘care’ that such institutions provided, not only through a

physical job that wore on the body but one reinforced with physical punishment,

which came to include emotional and sexual abuse, and poor food and living

conditions……

There

are significant variations between the institutional care described here for

the nineteenth century and a contemporary welfare state that encourages users,

as much as possible, to remain outside ‘the system’. The capacity for ‘the

state’ to control every dimension of a person’s life today is significantly

reduced; conversely, the ability of those in need to fall into service ‘gaps’

as they cannot access services or negotiate bureaucratic systems, is in some

ways increased. Nonetheless, there are parallels in the operation of both

systems that should give contemporary policymakers pause. Abusive care does not

just emerge from individual perpetrators, from the institutional model, or even

a lack of policies on staff-client relationships, but also from the wider

values and beliefs that shape the production of welfare systems; from the

financial and emotional investments that we place in institutions; and from the

corruption or occlusion of institutional targets and goals.

Ensuring

that the ‘cruel’ practices reported of current systems do not become systematic

issues on the scale of previous institutional abuses therefore requires not

just monitoring a few rogue individuals, but a clear goal about what our

welfare systems should achieve. The needs and interests of service users should

be placed at their heart, coupled with a significant social, cultural and

political investment in ensuring that goal is achieved. All other goals and

targets for welfare service providers, especially their frontline staff, should

be secondary to that and carefully designed so as not to interfere with that

end. With rising rates of poverty, homelessness and illness, welfare systems

look to continue to hold a central role in society for the foreseeable future.

It is imperative that the abusive practices of previous ‘caring’ regimes are

left firmly in the past.

Having failed to walk the walk Nationals MP & Australian Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources is belatedly trying to talk the talk

Well the

Nationals are out there trying to ‘spin’ their party as reasonable and balanced

in the hope of repairing political damage caused by the recent Ministerial Code of

Conduct-Use of Parliamentary Entitlements scandal.

This was former

National Australia Bank rural financial adviser, Nationals MP for Maranoa since

July 2016 & Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources since December

2017, David Kelly Littleproud.

The

Sydney Morning Herald,

2 March 2018:

The heir to Barnaby

Joyce's portfolio has declared he has nothing against renewables, believes

climate change is fundamentally reshaping agriculture, and called on city

dwellers to wake up to the economic heavy lifting being done by Australia's

farmers.

David Littleproud, the

banker who came within a couple of votes of snatching the Nationals leadership

last week, has no intention of emulating the former deputy prime minister.

"I am in favour of

renewables, make no mistake," he said. "It will mean we will have

cleaner air to breathe, there is nothing to fear in that."

The Agriculture

Minister, who party leaders hope will appeal to a new generation of voters,

said renewables needed to be brought in a way that "doesn't impact someone

being able to put a light on or a farmer being able to put a pump on".

"The stark

reality," he said, is farmers had been trying to deal with the effects of

climate change since they were "putting till in the ground".

The 41-year-old rejected

calls from environmentalists for an agricultural climate change adaptation

plan, but says that's only because farmers will need to do it themselves or

risk losing their crop.

His comments mark a

relatively climate-friendly shift from Mr Joyce, who promoted Mr Littleproud

into cabinet before Christmas....

What David

Littleproud does not say is that he has never voted against the

Liberal-Nationals party line in the House of Representatives to date.

Which means

he is on record as voting against:

And voting

for:

Tighter

means testing of family payments

Then there is the question of a potential for conflict of interest as the minister responsible for water resouces. Given his father-in-law owns one of those farming operations which allegedly have largescale unapproved earthworks which effectively dam floodwaters for unmetered water harvesting.

Then there is the question of a potential for conflict of interest as the minister responsible for water resouces. Given his father-in-law owns one of those farming operations which allegedly have largescale unapproved earthworks which effectively dam floodwaters for unmetered water harvesting.

Somehow I don’t

see Littleproud making much headway with what he calls “a new generation of voters”.

Labels:

hypocrites,

National Party of Australia,

propaganda

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)