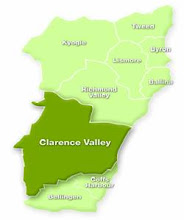

According to the 2021 Census, around half the people aged 15 years of age and older living in the seven local government areas of north east New South Wales have personal incomes averaging from $0 to $645 a week - which is way below the state average of $813 a week and the national average of $805 a week. Included in these figures would be the individual weekly incomes of those local residents who receive full aged pensions.

One sometimes sees media coverage that describes this part of the state as a low income region. Indeed, the region made NCOSS mapping of economic disadvantage - coming in at between est. 8.7% to 21.3% of the population experiencing economic disadvantage across the region in 2016. By the same token, in 2016 the NSW Government rated the region's local government areas on the "Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage" (IRSAD) as between only 1 to 8 points where "1" represents most disadvantaged and "129" least disadvantaged relative to other state local government areas.

We live in a beautiful region but are not unaware that life can be a quiet struggle for many in our communities. Sometimes it is even ourselves, our own families and friends who struggle.

It should come as no surprise that when poverty in Australia is officially defined, none of those doing the defining are classed as poor or living in poverty.

Sometimes it seems the voices of those with no incomes or low incomes are confined to short quotes in submissions made to governments by registered charities and lobby groups.

So how, by way of example, are those living below a current poverty line doing financially in 2022, according to the professors, researchers and statisticians in one self-styled “pre-eminent economic and social policy research centre”?

Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research,

POVERTY LINES: AUSTRALIA, MARCH QUARTER 2022, July 2022, p. 4 of 4:

|

| Click on image to enlarge |

Although this March Quarter comparison table gives an indication of disposable income it is uncertain if it takes account of rising inflation in 2022, given the only table included in the report which factors in Cost Price Index ends its calculations in 2020-21.

What it does calculate is that total maximum weekly disposable income in all but one of the pension and allowance categories is well below an Australian poverty line established in 1964.

However, in doing so the report attempts to minimise the lived experience of others by, in the first instance by broadly assuming that all cats are black in the dark and differences in individual circumstances don't matter and long as final percentage totals reach 100.

As one example. Not every single lone aged or disability pensioner who rents and is eligible for rent assistance actually receives rent assistance as disposable income or that such rent assistance amount is credited to their actual real life cash rent payments. In New South Wales alone it is likely that somewhere in the vicinity of 58,924 lone pensioners who rent are affected. That number of NSW aged and disability pensioners are likely receiving a total weekly disposable income derived solely from welfare payments which is not as the report suggests $59.49 above a poverty line in 2022 but in fact is an est. $11.91 below that same poverty line.

In the second instance the report minimises the lived experience of others by choosing to define all those receiving federal government cash transfers through Centrelink as being better off in March Quarter 2022 than they were in the last 49 years up to 30 June 2021.

The sources referred to, the many qualifications applied in compiling this data or even the contents of the four tables, will not be what media commentators, political advisors and public servants take away with them after reading.

No, what will be remembered is the impression given that all pensioners live above the poverty line instead of that most live in deeper poverty than that benchmark and the statement; “Put another way, the real purchasing power of the income at the poverty line rose by 60.7 percent between 1973/74 and 2020/21.”

BACKGROUND

Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research,

POVERTY LINES: AUSTRALIA, MARCH QUARTER 2022:

What are the Poverty Lines?

Poverty lines are income levels designated for various types of income units. If the income of an income unit is less than the poverty line applicable to it, then the unit is considered to be in poverty. An income unit is the family group normally supported by the income of the unit.

How the Poverty Lines are Calculated

The poverty lines are based on a benchmark income of $62.70 per week for the December quarter 1973 established by the Henderson poverty inquiry. The benchmark income was the disposable income required to support the basic needs of a family of two adults and two dependent children. Poverty lines for other types of family are derived from the benchmark using a set of equivalence scales. The poverty lines are updated to periods subsequent to the benchmark date using an index of per capita household disposable income. A detailed description of the calculation and use of poverty lines is published in the Australian Economic Review, 4th Quarter 1987 and a discussion of their limitations is published in the Australian Economic Review, 1st Quarter 1996.

The Poverty Lines for the March Quarter 2022

The Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research has updated the poverty line for Australia to the March quarter 2022. Inclusive of housing costs, the poverty line is $1,148.15 per week for a family comprising two adults, one of whom is working, and two dependent children. This is an increase of $5.16 from the poverty line for the previous quarter (December 2021). Poverty lines for the benchmark household and other household types are shown in Table 1.

The Poverty Lines are Estimates

As has been stated in paragraph 2, the poverty lines are based on an index of per capita household disposable income. The index is calculated from estimates of household disposable income and population provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Because the index is based on estimates, the poverty lines themselves will be estimates. As more information becomes available, the ABS may update population and household disposable income estimates for previous quarters. Whenever these estimates are changed, it is necessary to re-estimate the poverty lines. Accordingly, in addition to providing estimates of current poverty lines, we provide sufficient information for readers to calculate poverty lines for all quarters dating back to December 1973.

|

| Click to enlarge |

How to calculate poverty lines for other

quarters

Table 2 shows the estimated per capita household disposable income for all quarters between September 1973 and March 2022. This table may

be used to calculate poverty lines for any quarter within this period. For instance, to find the poverty line for the June quarter 1996 for any household type, multiply the current value of its poverty line by the ratio of per capita household disposable income in the June quarter 1996 to that in the current quarter; that is, the poverty line for a benchmark household in June 1996 would be 1,148.15 × 346.11 / 977.25 = $406.64.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Relative poverty and the cost of living Updating poverty lines according to changes in per capita household disposable income means that the poverty lines are relative measures of poverty. As real incomes in the community rise, so too will the poverty lines. The value of the poverty lines will therefore be reasonably stable relative to general standards of living, but may change relative to the cost of living. An alternative method for updating poverty lines is to use a cost-of-living index, such as the ABS Consumer Price Index (CPI). Poverty lines generated in this way are absolute measures of poverty. The real purchasing power of the income at the poverty line is maintained, but it may change in comparison to general standards of living. Table 3 compares annual movements in the poverty line for the benchmark income unit between 1973/74 and 2020/21 updated in these two ways. The table shows that, by 2020/21, an income unit whose income was adjusted to match movements in average household disposable income would have 60.7 per cent more income than one whose income was adjusted to match movements in consumer prices. Put another way, the real purchasing power of the income at the poverty line rose by 60.7 per cent between 1973/74 and 2020/21.....

Full PDF document online here.